I've been told that I’m going to hell more times than I can remember.

It’s actually been quite a while since someone has reminded me of my fiery destination, but I thought of the common refrain — which I’d heard so many times in my youth — when I visited a church last week to attend David’s holiday choir recital.

In truth, I've only gone to church a handful of times. I was raised by a mom who's a non-practicing Catholic, and a dad — an uncomplicated Scotsman — who sees no reason to believe in a higher power without sufficient proof.

While religion was more or less absent from the Ilgunas household, I was surrounded by religion. The Western New York town I grew up in was a melting pot of Italians, Germans, and Polish, and almost all of my schoolmates were Lutherans and Catholics, with a few Baptists sprinkled in.

The first time I was told that I was going to hell was as a young boy when a couple of Lutheran schoolmates condemned me for how I spent my Sundays. I was confused by their disapproval. I loved my Sundays: I’d sleep in till 11 a.m.; my mom would make me and my brother waffles; and I’d idle the day away watching football or playing hockey. Not once did I think I was missing out on anything.

But when I was in the third grade, my mother — who was second-guessing her carefree approach to my religious education — sent me to a Bible camp for the summer. I remember having a fairly good time, though my bunk’s counselor kept asking me if I wanted to talk about my “bed-wetting” problem after I'd left a pair of wet swimming trunks to dry on the mattress.

Each night there’d be a service, and the pastor would tell us all about heaven and hell. We were given a fairly cartoonish characterization of the afterlife: he said we’d either spend eternity with our loved ones in heaven, or have our asses habitually branded by Satan in hell. He told us that we were going to hell if we didn’t accept Jesus into our hearts.

The pastor gave those of us who hadn’t accepted Jesus the opportunity to do so at the end of each service. The few who could be counted as heathens — myself included — were encouraged to leave their pews and endure the long, lonely walk up the aisle and onto the stage as everyone looked on. I remember thinking that I was probably the only one in the whole church who didn’t have Jesus in his heart. I wanted so much to be on that stage! Though, at the same time, I was terrified of getting up in front of everyone. On the final night of camp, another boy in my bunk — also destined for hell — asked me if I wanted to join him on the stage at our final evening service the next day.

We both nervously got up and walked up the aisle. One of the counselors met us and made us kneel down. Together we recited a passage from the Bible. And that was that. Jesus was in my heart.

I came home fervent and wild-eyed. I prayed each night, read a special "kid's Bible," and warned my unresponsive father about his soul's destiny. But now that I was no longer isolated at Bible camp, I was subjected to a new kind of brainwashing: a constant stream of secular TV and hours of mind-numbing video games. I quickly forgot about Jesus, kicking him out of my heart, locking the door, turning off the lights, and rejoining my father on the couch on Sundays.

I always had friends, but I was a solitary child from a young age, coveting the time I had to myself. Between my solitary nature and my parents' “neglect,” I was able to develop some of my own beliefs in the absence of formal religious guidance. It wasn’t long before I became skeptical about the beliefs my schoolmates had thoughtlessly adopted.

While many look down on parents who don’t provide their children with proper religious training, I couldn’t have asked for a better upbringing. I had no choice but to craft my own morality, which I based not on some dusty set of rules, but on personal observation and reflection.

Still, whenever I openly criticized religion in front of my mother, she’d castigate me and warn me that, because of my beliefs, I’ll never be able to find a “nice Christian girl.” At first, this worried me a great deal. It seemed like all the girls in my high school were religious. What was a non-Christian girl even like? I feared I’d have to one-day settle for some freak with a blue Mohawk, a face full of jingling piercings, and no discernible sexuality.

But it was just the opposite. I was quiet and sweet-hearted, and it seemed like the only girls I liked and who liked me were the diehard Christians. My first two girlfriends were very religious.

The first — a kind and gentle soul — was known to quote Biblical passages in moments of intimacy to remind herself of her vow of chastity. The second was a hardcore Baptist. I was aware of her zeal before we made our relationship official, and while our differences gave me pause for thought, I figured it would be close-minded of me to not get involved with someone solely because of her religious affiliation.

She carried in her purse a heavy, full-size Bible that affected the way she walked. We were sitting on a bench at Niawanda Park on a sunny spring day, looking over the mighty Niagara River.

“Do you see how wide this river is?” she said. “If the width of this river is eternity, this is how long of it you spend on earth.” She said this while holding her thumb and forefinger an inch apart.

“You don’t want to spend eternity in hell, do you?”

I was 19 and smitten despite our differences. We rarely brought up religion — as we knew it was a contentious subject that threatened the relationship — but occasionally she couldn’t help herself. Late one night, we were sitting in my ’87 Dodge Aries in a McDonald’s parking lot drinking chocolate milkshakes. The scene was characteristically American: fast food, a car, a panting male, and a female oblivious to the intensity of her boyfriend’s raging desires.

While I was hoping to move past the first base plate I’d been bolted to for months, she had other things in mind. She began describing Christ’s crucifixion in vivid detail, bursting into tears halfway through. I tried to console her, but she held up her Bible, announcing that me and my earthly pleasures were “obstructing her walk with God.”

“You just don't how it feels to have Jesus inside of you,” she muttered hopelessly. It was true: I didn’t know what it felt like to have a man inside me, and I wanted to keep it that way. But Jesus, from what I knew, was a pretty cool guy, and a human being as good as any to model your life after. But for a country obsessed with Jesus — perhaps the most famous ascetic in history — I found it awfully strange with how many Christians there were, yet so few ascetics. In fact, these Jesus worshippers — with houses full of junk and hellfire on their breaths — seemed awfully un-Jesus-like. The paradox baffled me.

So began a period in which I despised Christianity, and all organized religions, really. Not only was religion restraining my sexual progress at the height of my virility, but it began to look more and more foolish. All this talk of heaven, hell, and some grandfatherly Caucasian in the sky just seemed so ridiculous.

In college, I thought more about religion and had engaging discussions with classmates. Those who still counted themselves as practitioners held far more enlightened beliefs than what I was previously exposed to. They interpreted religious texts figuratively; they respected other people’s beliefs; and they were focused more on the social benefits of a church, and less the superstitions and crazy rituals.

Religion, I thought, could go to hell.

When I moved to Coldfoot after college, my best friend Josh and I — to entertain ourselves and others — created, what we thought was, the first ever “Debaptism.” Josh and I were both baptized as babies, and we each looked with disdain at the ritual since it was carried out with neither our awareness nor consent. So we figured we could right a wrong with a ridiculous ceremony.

I spent three days planning out the ceremony and writing the script in the style of the King James Bible. I would be the Debaptiser, and Josh was to be the debaptised.

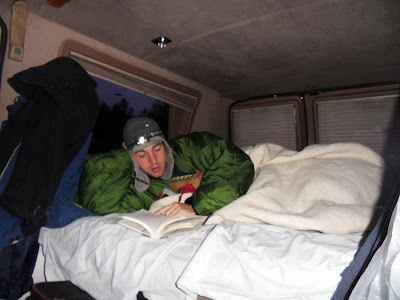

We slipped invitations under everyone’s door, decorated my room with every candle we could find, and played a CD of chanting monks as everyone got comfortable on my two twin beds that served as pews.

The ceremony was held at night, and for that whole day I didn’t let anyone see me so as to create an air of solemnity around the ceremony and mystery around the Debaptizer.

Unbeknownst to the congregation, I was standing alone in a vacant room across the hall, draped underneath a white bed sheet that functioned as a shawl. Much to my surprise, everyone who received an invitation showed up, all wearing the nicest outfits they could put together. I could hear their babble through the paper-thin, wood-paneled walls. I paced across the room, reciting my lines.

In the room where the debaptism was to be held, Josh stood in the center, surrounded by everyone else. He wore a dress shirt and tie, and held a candle (signifying nothing, really) as he awaited his purification.

One of the young women who I delegated as a "holy attendant" came rushing into my cell, warning me that the crowd — of a dozen or so — was beginning to get antsy.

“We need to start this!” she exclaimed. “They’re ready for you.”

“Good,” I said, stoically, staring straight ahead. “Thence I shall wait another five minutes.”

She gave me a confused look, and scurried back to the room to make sure everything was in order. The truth was, I was starting to get nervous. I thought it was ridiculous that I was letting myself get all worked up about an absurd ritual that I had created. But there were a lot of different religious backgrounds represented in our audience — a couple of Catholics, a Mormon, a Muslim, an atheist, as well a new-age mystic — and I certainly didn’t want to offend any of them. But it was no time for second-guessing. I had to go in.

The music and lights were abruptly turned off. I walked in with slow, powerful strides.

The room was dark and candlelit. The audience, I could tell, wasn’t sure whether to take me seriously or laugh. My holy attendant stood behind me and removed one white bed sheet, only to reveal another white bed sheet beneath. Josh was standing in the middle of the room trying to suppress a grin. My face, under my hood, was turned to the ground. Slowly, gravely, I lifted my eyes to meet Josh’s. My attendant, at this point, hit the play button on the CD, changing it to my grandiose Last of the Mohicans soundtrack.

“We gather here today,” I beamed loudly, “to renounce the forced corruption of thy childhood, beginning with thy compulsory participation in a religious sacrament, when thou wert too young to refute. (Gimme a break—I wrote this a long time ago.)

“We shall call this ritual, ‘Debaptism,’ and I welcometh thee, my son, today, here where thou hath chosen to ceremoniously discard, what was so unrighteously forced upon thee.

“From thy womb thou wert anointed in water called holy, forced into a cult superstitious in character, and branded as Christian—all against thy will and knowledge. Theretofore — confined in a fortress of antiquated concepts, captive in a dungeon where enlightenment wert disallowed from coloring thy pallor — thou wert shackled in the blinding darkness of religion.

“Baptized thou wert to walk in clouds that did not exist, told to be one with a god who was not there, and forced to continueth the very traditions that clash with basic tenets of logic, reason and nature.

“However… through education, observation, and reason, thou hath awoken to the realization that the only pearly gates thy deceased form shall pass through are those of a cemetery.

“Today I shall release thou from my lingering burden that thou hath shoulderethed for ages. Thou art here today to celebrateth a new beginning.

“Now… I shall striketh the lord from thee…”

At this point I blew out the candle in Josh’s hands. What followed was a bizarre series of rituals: more candles lit and candles blown out; Josh was forced to go down on all fours; I even slapped him across his face at one point. Finally, I poured some water over his head (that I’d obtained from the bathroom sink) to ceremonially cleanse him of his original baptism.

I told him that he's been “purified,” and, to close the ceremony, I read this Buddhist quote:

“Do not believe in anything simply because you have heard it. Do not believe in anything simply because it is spoken and rumored by many. Do not believe in anything simply because it is found written in your religious books. Do not believe in anything merely on the authority of your teachers and elders. Do not believe in traditions because they have been handed down for many generations. But after observation and analysis, when you find that anything agrees with reason and is conducive to the good and benefit of one and all, then accept it and live up to it.”

The audience erupted in applause that echoed through the halls. Josh was given gifts, Mormon and Muslim came together, and we all got thoroughly soused on whiskey and Miller High Life. The Debaptism was a stunning success.

As I listened to David and the choir sing, I looked over the audience and felt a twinge of envy. Everyone knows each other in this room, I thought. They show up every week and shake hands. Someone will ask someone else how so and so is doing after their surgery. One family will invite another over for dinner. It reminded me of my distance from my family, and the neighborhood of man that I’ve done without all these years. I looked at some of the pretty girls singing on the stage and fantasized about what it would be like to settle down with one of them and embrace a more conventional version of the simple life.

There are of course many good things about religion: the sense of community it fosters, the sense of charity and compassion it often encourages, or the comfort it gives to the bereaved and those on their death beds. And of course I don’t really think that religion should go to hell. Anyone with a set of beliefs and morals is religious in their own way, even if those beliefs don’t align with those of a major sect.

However, the sort of religion most in our country practice seems destructive. Not only is Christianity wreaking havoc on our planet (

there is a stark correlation between religiousness and climate change denial), but it smothers the individual soul. When we blindly accept the dictates of a religion, we are inhibited from living according to our own peculiar natures, from following the choreography of our consciences, and from seeking our own versions of success and happiness.

On a personal level, believing in heaven or hell or in a god or gods is pretty inconsequential. But when a whole society is deluded, the consequences can be huge. Not only does religion encourage conformity, but complacency, too: We trust hypocritical

religious leaders and politicians; we place our faith in

flagrantly mendacious news outlets; we don't take

our president seriously because we think he’s a terrorist. (Do I think religion is the sole factor in the crazy and destructive things our country believes in? No, but I wouldn't be surprised to learn it's the biggest factor.)

This, unfortunately, is how religion works in the real world.

If religion has the tendency to fashion us into conformists and prepare us to be deceived, then heresy encourages individuation and helps us defend ourselves from lies. Heresy, though, can be alienating and unsettling.

Many prefer religion because it provides us with prepackaged principles and a well-worn path. Questions don’t need to be asked, mysteries don’t need to be solved, and as long as we say our prayers, read our Bibles, deny gays equal rights, multiply, spread, and subdue the earth, we get to go to heaven.

But without the path that a religion provides, one must blaze his own. And there is, I feel, no better way to spend one’s youth than doing just that.