“It sounds like your inner Odysseus is lost at sea,” said Liam, the prize chef of Deadhorse Camp.

I’d just let out a sigh—a desperate, pleading, “kill-me-now” sigh—for the third time in the hour. With a wire brush, I’d been trying to scrub dried specks of mashed potato off the rim of a large metal stirring bowl.

I’d been working the evening “dish shift” almost every night for the past three weeks. And I’d never felt so purposeless. Somehow, over the course of the summer, I’d gone from an inspired and well-meaning “writer in residence,” to tour guide, to dishwasher. It was as if I was on some cruel Scrooge-like, time-traveling tour, visiting my previous jobs, each demanding less skill and responsibility than the previous.

After a while, I no longer felt like a writer, or a vandweller, or some principled Thoreavian; I’d momentarily forgotten "me"; I was now nothing more than a dishwasher. I cursed more. I told crass, tasteless jokes. I wore smelly, stained, soup-splattered shirts. I spent my nights drinking cheap beer, watching TV, and the beginnings of a paunch began to bud out of my belly. Dishwasher. I’d grown my beard out, but not for the usual reasons—facial warmth and aesthetic beauty—rather, my patchy brown scruff was evidence of a rapid degradation of self-worth, which made all established habits of hygiene and physical upkeep seem pointless. I felt bitter and demoralized; an invisible automaton, a dishwasher.

I knew my mental health had become ill when I—upon dropping a tray of turkey lunch meat—didn’t maniacally curse as I normally would in such instances; rather, I just stared at the meat sprawled across the floor silently, my frustration silently approaching the brim of its containment tank, like brown water nearing the rim of a clogged toilet ready to spill over in a deluge of messy, violent anger. I just hope I’m nowhere near the knives when it happens, I thought.

Then Liam said, “We need to get out. We need to packraft the Sag and see the ocean.”

And so we did.

Liam said it would be a five mile hike to the Sag River. We’d packraft north (two or three miles) to the Arctic Ocean, then we’d paddle west across the coast and descend south down another branch of the Sag to Deadhorse.

Sounded like a plan to me.

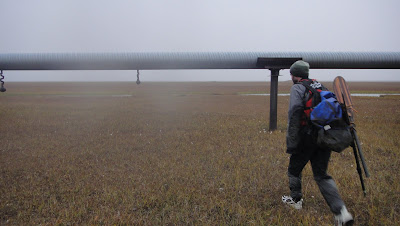

Donning dry suits and toting light day-packs, we hiked out over the flat, hard, easy-on the feet tundra. The fall foliage was colored with squash yellows, apple reds, and pumpkin oranges. Most of the birds that had been up here had already migrated south, but there were still vestiges of the summer swarms of flying life: we spotted snowy owls, flamboyant loons, floating gulls, flocks of geese, and gaggles of ravens. Off to the north—through Liam’s binoculars—we saw a golden eagle (or some giant bird) on the ground that flapped its wings at a ghostly-white arctic fox obnoxiously running laps around it.

We inflated the packrafts and let the Sag—swift and powerful at these northern latitudes—carry us to the Arctic Ocean. Except the ocean wasn’t a mere couple miles away as Liam thought it was. We’d stayed on the river for three hours, and while we expected to see the ocean after each bend in the river, we never did.

Because of our late start and the longer-than-anticipated time we'd spent on the river, we began to appreciate just how late it was getting and how low on time we were. (We had to be back in camp by tomorrow morning for our kitchen shifts.)

And then, on the river, just ahead, we spotted something white and bulbous. We both pulled over to the bank, quickly and instinctively.

“Do you see that?” I asked Liam.

He took out his binoculars and glassed the object. “I don’t know what it is,” he said, “but it’s big and it’s moving.”

I will openly admit that I have a fear of bears, but the polar bear—the bear I know the least and the bear that is, reputedly, the most fearless of the ursine family—was enough to make me think about showering my eyes with pepper spray, right then and there, just so I didn’t have to watch it come and maul me.

Whatever it was, it wasn’t worth paddling past. We decided to raft to the other bank, deflate the packrafts, and get the hell out of there. As I feverishly deflated the raft and sloppily strapped it to the outside of my pack, my frozen hands and saturated gear coated in rough sand, I watched the polar bear, which actually turned out to be a gull, leisurely float down the Sag passed us.

One’s sight, we learned, can no longer be trusted on this flat, lunar, northern landscape.

Okay, no polar bear, thank god, but we had more than enough problems. For one, because we thought this would be a short day-trip, we didn’t have any overnight gear: no sleeping bags or tents. And because we were so far north, there would be no wood to start a fire. And, after looking at my GPS, I saw that we had a 12-mile hike back to Deadhorse, which would actually be more like 15 when you consider that we would have to walk around ponds, lakes, and tundra bog. And our biggest problem: it was getting late, dark, and foggy, and we had to illegally walk through the vigilantly monitored, hyper-secure Prudhoe Bay oilfield—the largest oilfield in North America that, before drilling started in 1977, held 25 billion barrels of oil. Hiking through the oilfield is strictly prohibited, and while we had no desire to break the rules, there was no way we could get around Prudhoe Bay. We’d have to sneak through.

And then I felt, for the first time in a long time, the pangs of panic. We’d walked a mile west, or where we thought was to the west, but when I looked down and picked up my pack that I'd set down for a moment, I’d forgot from which direction we’d come and to which direction we were heading. I did a 360. And then another 360. Everything was flat. The sky was an overcast gray. Everything looked the same, in every direction. I pulled out my GPS and compass and they each seemed to be as disoriented as I was. Sit down, Ken, and calm down, I told myself.

Eventually a light popped up on the horizon. It was one of the many oilfield facilities, which we knew was to the west. It was the ugly, all-seeing eye that would monitor our impossible jaunt through what felt like Mordor. (After I made this reference to Liam—a fellow Tolkien fan and another overeducated English major—we proceeded to use LotR references to describe our situation, forcing us to periodically acknowledge our nerdiness.)

To stay warm, we walked inside our wind-resistant dry suits. Night supplanted day, and a frosty mist clung to facial hair. On the edge of a lake in front of us sat a giant, bull caribou, bearing a curled crown of skyscraping antlers that were orbited, elliptically, by two bat-like short-eared owls, both of which—after the caribou had regally trotted off and disappeared into the fog—came to inspect us, flaplessly hovering above us like kites.

In front of us was one of many oil camps. It was a small, metallic, rectangular facility with about a dozen outdoor lights. We were all whispers now, wary of being caught and having to deal with the possibility of an interrogation or, at worst, a fine, for trespassing. It was close to midnight and dark, so we thought we could slip by undetected. As we neared the building, we saw some humanoid-like movement. A spotlight clicked on; whoever was manning the light drew figure eights onto the tundra. We stood still, but eventually he trained the spotlight directly on us. We were shocked that he’d spotted us because we were still a good distance away.

“We’re fucked,” I said.

“Just stay still,” Liam said. “If they come near, just lay on the ground.”

“What? I don’t know man. Maybe it would be better if we just gave in if they’ve already caught us.”

We debated what we should do in whispers, remaining perfectly still as the light shone upon us. Because it didn’t appear that they had any plans to capture us and because we thought that there was a possibility that they merely thought we were caribou, we recommenced hiking, each of us lengthening our strides and adding an alarmed briskness to our gait.

We reached an industrial road and placed our footsteps carefully and in sync with one another's to lessen the volume of our boots crunching atop the gravel. We ducked under an oil pipeline and continued on.

Disaster was averted, but we were far from home-free. Ahead of us were several more well-lit facilities that we’d have to get around. We walked next to wells and pipelines and a gravel road—the horizon of Prudhoe Bay was lit up with fool’s progress, a spider web of industry, an Ayn Rand wasteland.

We were close to the next facility, walking parallel with a road. There were lights everywhere, in all directions. White lights, orange lights, red lights, blinking lights, the lights of trucks on the prowl, moving from facility to facility. We couldn't tell which lights were close and which lights were far. And the buzz of machines was ubiquitous. This foreign land never felt so eerie. Here we are, intruders, sneaking through the land of other intruders.

As an augury of ugly things to come, atop a pingo—which is a mound of earth-covered ice—the silhouette of an arctic fox appeared. It howled (which sounded more like a raven's crow), and we nervously strode past it, worried that its cackles would call attention to our location.

We were within a stone’s throw of the facility and the gravel road. I kept an eye on the fox, but when I turned my head south, I saw Liam sprinting away, his arms pumping furiously, piston-like, going as fast as he could over land we couldn’t see beneath us, his packrafting oars rattling with each footfall. I joined him, sprinting across the tundra until I was out of breath. We dove behind another pingo and I asked him why we were running. “You didn’t see it?” he said. “There’s a truck with a spotlight right behind us.”

He was right. On the other side of the pingo, the truck had come to a halt at the end of the road. We could hear its motor rumbling and could see its spotlight oscillating from side to side, its beam causing a white halo to form around the tip of the pingo we sat behind. It was obvious that someone had spotted us at some point. And now they were on the lookout for us. This is it, I thought. All they have to do is get out and look over this pingo. And we’re caught.

But they never did. We continued on through night and fog, around lake and across the other waist-high branch of the Sag.

The trip was a catastrophe; we didn’t make it to the ocean and we ended up back in camp after 3 a.m., prohibiting us from getting a good night's rest before our shifts in the morning.

“This is the best experience I’ve had in a long time,” said Liam.

“I know. Me too.”

***

The Sag. Somewhere to the north was the Arctic Ocean which we never got to see.

Here's packrafting guru and prize chef, Liam (which isn't his real name).

My pack is actually pretty small and light, but looks huge in this picture. (After we got off the Sag neither of us had any feeling in our hands, so I couldn't help but sloppily strap the raft to my pack.)

One of several pipelines we crossed.

The mythic caribou.